Adam Low is the director of the recent BBC2 Arena documentary, Seamus Heaney and the Music of What Happens. Here he describes meeting the Heaney family for the first time and how he went about making this very personal and intimate documentary.

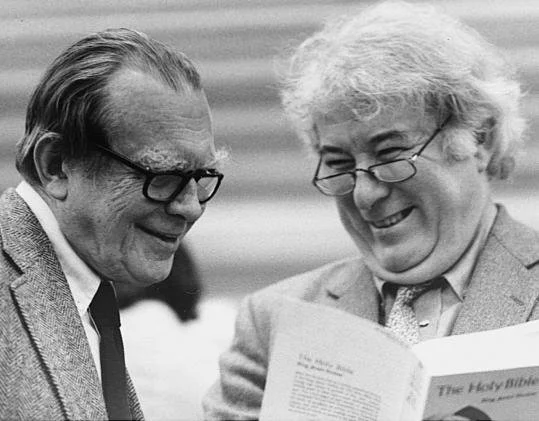

Photograph by Antonio Olmos.

On 25th March 2009, I flew to Dublin with Matthew Evans, the former CEO of Faber and Faber, and my producer Martin Rosenbaum to film Seamus Heaney for a BBC Arena documentary about TS Eliot. Matthew and Seamus were old friends so it was a relaxed and informal encounter. Sitting in his favourite green-winged armchair, Seamus spoke wonderfully about Eliot, for whom he had huge admiration, and read, hypnotically from the end of ‘The Fire Sermon’ in The Waste Land. When we left he signed a copy of his latest book, District and Circle, ‘for Adam at the centre of the Eliot circle in the Heaney district – welcome’.

At the time he must have been working on another collection, the marvellous final volume Human Chain, which came out in 2010. He was warm, funny (he ribbed Matthew by calling him Lord Evans) and couldn’t have been more generous. Of course it was a fleeting encounter, but meeting him made a huge difference when the idea arose to make a film about him and his work. Even a brief connection was enough to infuse the whole project with his character and it allowed us to make a film that was far more intimate than it might otherwise have been. It’s a mysterious thing, but somehow he became an abiding presence, and his own naturalness and lack of grandeur was reflected in a film that is simple in its elements but packs a great emotional punch because it is so personal.

Few poets have written with such clarity about their own lives, and it became apparent to me almost immediately that it would be possible to make a film that used Heaney’s poems themselves to tell the story of his life; but in order to do this we needed the support of his family and friends. The approval of his wife Marie was crucial – but would she be happy with the idea? Seamus died suddenly in 2013 and even four years later Marie and his family might not want to take part in, or give their consent to, another film about him (and by extension about their own life together). The important thing was to make the right kind of approach and to make it clear that we would only proceed if the family were happy with the idea.

Luckily our co-producers in Belfast, Michael Hewitt and Dermot Lavery, knew a good friend of the Heaney’s, the composer and musician Neil Martin, who was able to mention the idea to them, and through a friend at Faber and Faber I was introduced to Seamus’ daughter Catherine, who arranged for us to meet with her mother and her brothers Michael and Christopher over lunch in Dublin. I sat next to Marie who regaled me with anecdotes about Seamus (most of which she said couldn’t go into the film). She also explained that she was only just emerging from the shock that followed Seamus’ death, and was still feeling very raw. Catherine had arranged for all the family to watch a film I had made the year before about WH Auden, to give them a sense of the kind of documentary we were proposing to make. Fundamentally, although they were very different poets, the fact that Auden’s poems were read extensively and prominently in the film appealed to Marie in particular, and she was enthusiastic about the prospect of a film that would do the same with Seamus’ work.

A month or so later we found ourselves in Bellaghy, the small town in Northern Ireland where Seamus grew up, and where his brother Hugh still runs the dairy farm, which their father inherited from his uncles. Bellaghy is the Bethlehem of the Heaney story, as it also contains the original farmhouse, Moss Bawn, where Seamus and his brothers and sisters (he was the eldest of nine) were all born. It’s an unprepossessing town, saved from obscurity by the recently built Seamus Heaney HomePlace, which houses a terrific exhibition about Heaney and puts on an impressive range of events that have transformed the cultural landscape of the area.

In addition to Hugh, we met three other brothers – Charlie, Colm and Dan – who all live within ten minutes’ drive of each other (a fourth brother, Pat, moved to Canada, but stayed in frequent touch, but very sadly he died while we were making the film). This is as close a family unit as it is possible to imagine, and we spoke to each of the brothers in turn. All of them have very clear memories of Seamus, and they helped us to interpret the poems he wrote about the family, and about the wider context of living in this part of Ireland. Charlie remembers the close relationship between Seamus and their father’s sister Mary, who lived on the farm; she was ‘a second mother’ to whom he dedicated several poems including the elegiac ‘Mossbawn: Sunlight’ about her baking the family’s bread. Colm took us to see a bog where peat or ‘moss’ is still dug for fuel, exactly as Seamus describes it in perhaps his most famous poem ‘Digging’. Dan read from ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’ about the intricate disguising of religious and political allegiance that still pervades life in the North, and talks about a cousin Colum McCartney, who was murdered by paramilitaries in 1975. Hugh recalls witnessing the tragic death of their brother Christopher in a road accident at the age of four, which became the subject of Seamus’ heart-breaking poem ‘Mid-term Break’.

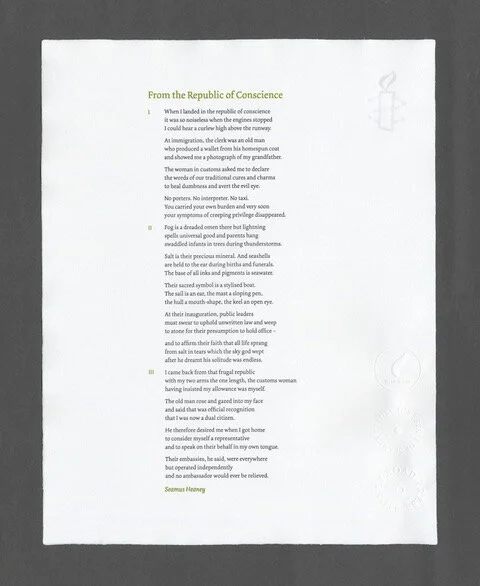

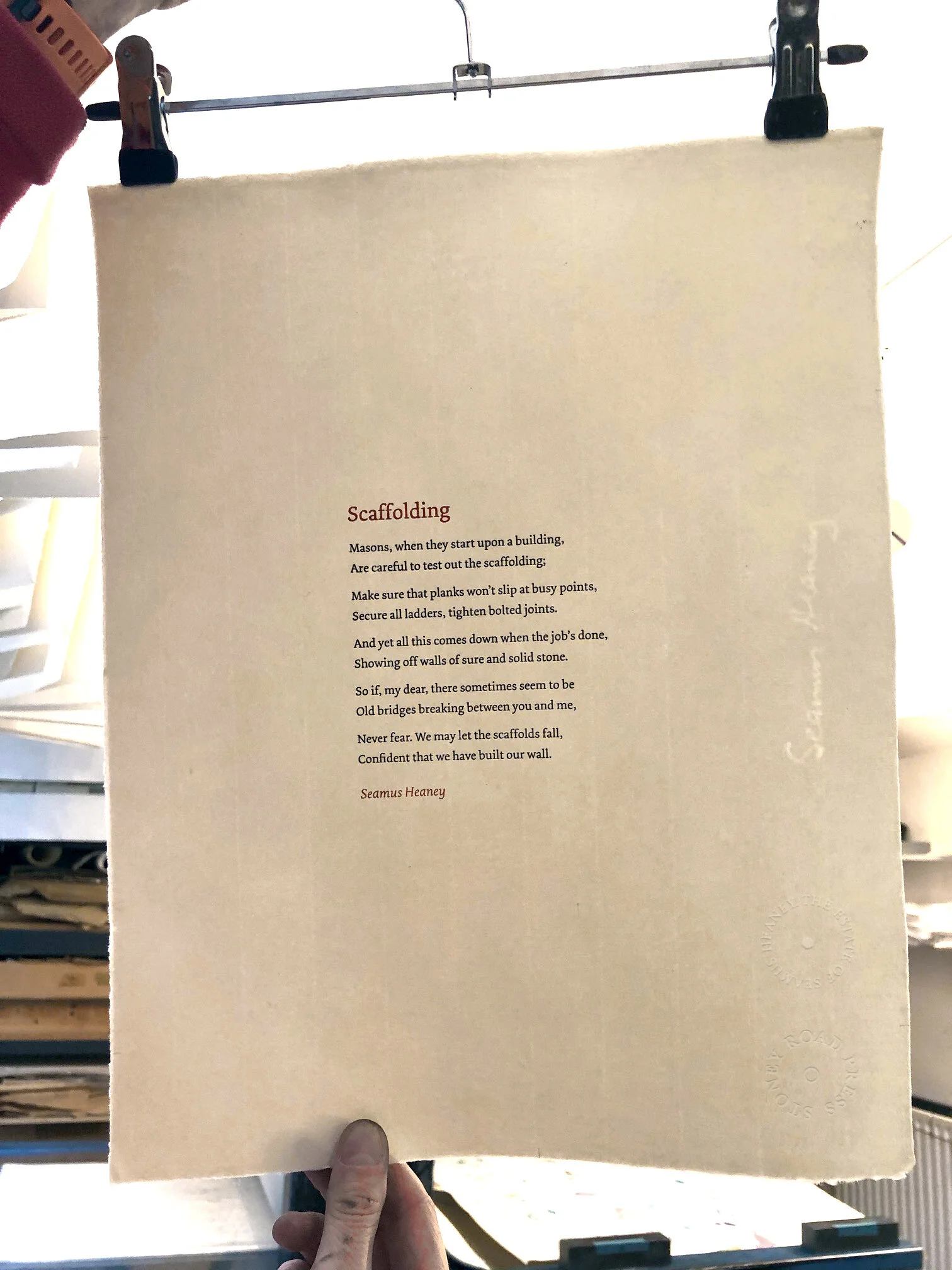

At the centre of the film there is a remarkable love story. Marie reads ‘Twice Shy’, the first poem Seamus wrote for her, about a walk they took together along the river Lagan in Belfast in March 1965, after which ‘I think we knew then, although we’re both fairly cautious people, that we would end up together – and we did, for over fifty years’. She became his first reader, and the dedicatee of his first collection of poems Death of a Naturalist, which was published by Faber and Faber in 1966. Seamus wrote poems for Marie throughout their life together (‘Tate’s Avenue’, ‘Wedding Day’, ‘The Otter’, ‘The Clothes Shrine’, ‘The Skunk’) many of which are extremely personal ‘I think a lot of the poems are subliminally erotic’ she says, adding ‘that’s fine!’. At Christmas 1983, Seamus hadn’t managed to buy Marie a present, so he wrote out all the poems he had written for her up to that point in a special volume, which she reads from for the first time. The poem she chooses is ‘Scaffolding’, which be wrote for her before their wedding and which today, she chuckles, ‘is read at virtually every wedding in Ireland’.

Seamus Heaney and the Music of What Happens is a production for BBC2. It is available online at BBC iPlayer.